The relationship between food consumption and the terminal endpoint of this food’s journey through the digestive tract is one that is well known. Put simply: we eat, we poop.

The facets of this complex interplay between our source of nutrition and our body’s assimilation and elimination of organic matter was originally explained to me by a giraffe puppet in a van parked in our school’s parking lot. While this may seem like the opening of a crime novel, one in which the next scene involves my parents finding my bed empty and a giraffe puppet left in my place, it wasn’t as sketchy as it sounds. The van was called the Life Education Van and the giraffe was called Harold, a character all us kids believed was real despite the fact that Harold only appeared from his hole in the van’s wall when the educator was pressed up against the same wall within arm’s distance of Harold. And despite the fact that Harold was clearly a puppet.

But except for the Victorian Government’s unique efforts to bring health education to primary school children, the mechanics of digestion is something not normally discussed in polite society. We invent euphemisms for it, saying socially acceptable statements such as: “I’m going to go wash up”, “I just need to relieve myself”, or “I’m going to drop the kids off at the pool.”

One of the first things you pick up as a new parent is that poop is no longer taboo. In fact, poop very quickly becomes a favourite topic of conversation. Some would even say an obsession.

Our journey into the defecation delights of our offspring began the first night in hospital. Due to the COVID restrictions at the time, I had been hustled out of the hospital and sent to my room like a misbehaving child, so I was sadly not there when Alex opened Roo’s tiny diaper and discovered the black sticky gold that is meconium. For the uninitiated, meconium is a baby’s first poop and is vastly different from the substance we’re more familiar with coming out of our backsides. It’s often described as a black tar-like substance, which isn’t something you expect to see leaking out of your newborn miracle of life. The upside is that it’s essentially odourless. The downside is the knowledge of what it’s made of.

Some of you may have already ventured down the thought-train of wondering how a baby that has previously never enjoyed a good meal has anything ready and waiting in his lower colon. It turns out that babies want to come out of the gate fully set up for that first delicious drink, and so in order to prepare their digestive system, they start taking small sips of whatever they can get their mouth around. Given that they’re suspended in a soup of amniotic fluid, amniotic fluid is what they drink.

This in and of itself is no great concern; amniotic fluid is a rather sterile substance. The problems start to arise when all this liquid they’ve drunk wants to come out, so their newly developed urinary system gets to work and pees most of it out, only it has nowhere to go except back into the fluid in which they’re suspended. But the baby still wants to practice their drinking so they guzzle it back down. And so the cycle continues.

But urine isn’t the only additive to their amniotic brew. Thrown into this cocktail is flaked-off skin cells, fine fur-like hairs that the baby sheds in-utero, and equal parts mucus and bile, all of which slides down their tiny throat to pool in the belly and kick start the first journey through the newly minted intestines. This collected, digested, and compressed assortment of ingredients are what make up the black diamond that is meconium.

It is this disgusting and oddly fascinating secretion that is the gateway drug into the addictive world of being a diaper detective.

When we first brought Roo home, his input concerned us more than his output. We were on the lookout for wet nappies, of course, but knew if we couldn’t get anything into him, there was no point worrying about what came out.

Breastfeeding is a challenge for anyone, and despite the fact that this is how we’ve evolved to survive during these early helpless months, there’s no guarantee it will actually take. We went in fully armed, baby courses completed, books read, and breast pump warmed up and ready to go. Thankfully, Roo inherited his parents’ appetite and willingness to eat anything put in front of him, and so took to the nipple with the same gusto Alex and I take to a punnet of ice cream. This meant we didn’t have to wait long for poop number two.

When that little brown stain appeared in the lining of his diaper, you’d be forgiven for thinking it was gold he was passing and not faecal matter given the sounds of celebration coming from Alex and I at this momentous occasion. We praised him on his cleverness, hoisted him aloft like the victorious hero that he was, then quickly returned him to the change table to avoid being peed on.

It wasn’t long before we had a shared google sheet drawn up to track his colonic expulsions, the document updated with the accuracy and diligence expected from my nursing days. Each movement was oohed and aahed over appropriately before being wiped up and thrown away. The one who had done the wiping would handover to the other, providing details on size, odour, colour, and consistency, and, on a good day, the anatomical locations the poop had managed to track to despite our boy being essentially stationary. His best effort was the base of the neck, which, I know, seems to defy the laws of gravity, but there you have it.

**GRAPHIC CONTENT WARNING** (You didn’t really think you’d get through this post without seeing poop, did you?)

Our super sleuthing showed that the pattern of pooping was not always consistent, with the average duration between soiled diapers being two to three days, but sometimes extending to as much as a week before we again mined that brown coal. On these occasions we would wait with baited breath at each nappy change, peeling away the layers of absorbent material, only to slump our shoulders and shake our heads at finding a urine-only deposit. Please let me make it clear: it was for the health of our child and the reassurance that his plumping was flowing as it should that we were so keen to discover his next poop, not some sick delight in adding to our defecation collection, like a twisted version of Pokemon Go. Gotta catch ‘em all.

Once we crossed the five day mark and the poop drought was still ongoing, we would begin to get nervous, imagining the giant mass that must surely be building in Roo’s large intestines. I would gently palpate his abdomen, feeling for any collections and watching for signs of discomfort. Roo would smile and drool, as happy as if he’d had his morning constitutional just minutes ago.

It was then that we would usually turn to the internet, which anyone living in the modern era knows can be an activity fraught with fear-mongering and misinformation, the equivalent of bathing in grease-coated water in an attempt to get clean. Nevertheless, we would dive into these depths, battering away sites convincing us of deadly diagnoses or miracle cures, to the haven of scientifically-mediated pages. It was here we learnt that it’s not uncommon for an infant to go a week without dropping their load and that it’s usually a sign of a growth spurt. Essentially, the baby’s body is working so hard figuring out the world and increasing in size that it uses every drop of resources available to it. Given there’s not a lot of bulk in breast milk in the first place, it leaves the bowels barren and any residual waste is disposed of via the urine.

When the drought finally broke and we would see that look of concerned concentration on Roo’s features that we had deduced meant our son was involved in some internal reorganisation, we would cheer as if the rains had fallen on the drylands and dubbed Roo with the title “Super Pooper.”

The joy in our new found hobby soured when Roo started on solid food. With carbohydrates, meat proteins, and fibre to fill out his downstairs cargo, those cute little near-odourless milky poops suddenly got an upgrade to proper stools, and while they didn’t match the volume of an adult voiding, they made up for it in strength of smell.

The other thing that changed was Roo’s sudden interest in what we were getting up to down there during a diaper change. I presume he reasoned that given we were paying so much attention to his undercarriage, there must be some event taking place in which he should participate. And so, as not to miss out, he would plunge his hands down into the mess and grab and squeeze whatever he could get his fingers on. Those fingers would then reach lovingly for our faces to caress our cheek or perhaps do some finger painting with this newly discovered medium.

This combination of increased odour and the risk of walking away with a poop handprint somewhere on your person cured us of our addiction and meant we instead would feel a trickle of dread every time Roo crawled over with a little extra junk in his trunk. Lately, while she’s prepping him for an outing, I’ve caught my wife whispering instructions to Roo to do all his pooping while he’s away, before handing him off like a loaded gun to the unwitting friend or family member kind enough to volunteer to babysit.

This stool story, of course, still has a long way to go as we face the future challenge of toilet training, but for now we will continue to wind our way through the wastelands, breathing through our mouths, fending off rummaging little hands, and praising our boy on a job well done, hopefully sending the message that every number two makes him number one in our book.

Next week’s topic: Year One

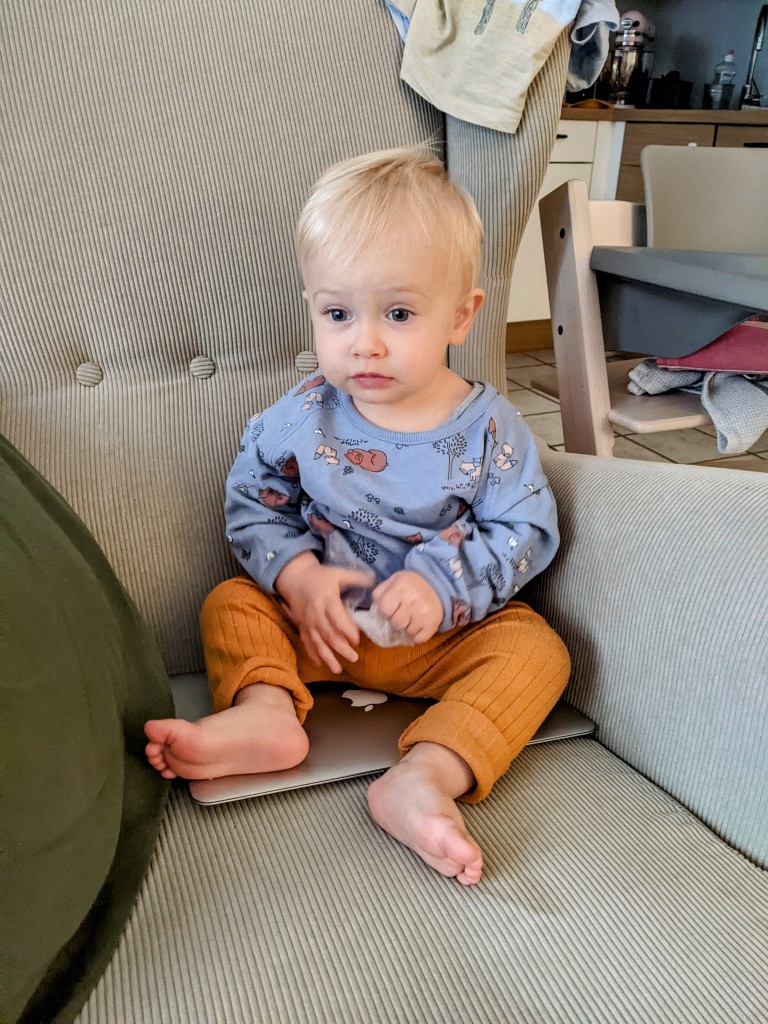

Hysterical Jon laughed so much I cried. Lucky Roo is so cute 🥰